Kindergarten Inquiry Project

First semester, I completed a kindergarten inquiry project. I was curious about the way that children communicated while playing with the Big Blocks, as at that centre they were both building structures and role playing. My choice of this particular topic, in large part reflects on my belief that play is necessary for young children to learn. This inquiry project/observation correlates to the OCT's Standard of Professional Practice as it involved research, communication and observation, and will inform my future teaching practices.

Focus statement: The way children play with Big Blocks is considerably different from the way they play with smaller sized blocks. The Big Blocks are located near the role playing centres, and are used in the creation of settings/props. Students use these centres to facilitate role play. While watching the children play, I noticed how the children were compromising and creating role play settings collaboratively.

Question: The kindergarten curriculum includes a strand for personal and social development. When kindergarten students play with the Big Blocks, in what ways is it helping them to build social relationships as they construct dramatic role play?

In this study, ninety one preschoolers from thirty-five months old to sixty-nine months old were observed. Social competence was measured by teachers. It was found that the amount and degree of intricacy of fantasy play affected competence, which is described as “popularity, social role-taking skills, social competence and observations of social behavior.” A correlation between peer social fantasy play and the development of social skills / building of social relationships is suggested. This article discusses how social fantasy play differs from other forms of play, and the types of social fantasy.

My observation will be focusing specifically on the social development that children undergo while playing with Big Blocks, especially as it relates to the Ontario Kindergarten Curriculum. This document will act as a guideline for what social development means in the Ontario Curriculum context.

Stagnitti, K. & Uren, Nicole. (2009). Pretend play, social competence and involvement in children aged 5-7 years: The concurrent validity of the Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 56, 33-40.

Stagnitti and Uren make the connection between play, the development of social skills and the ability to sustain involvement in classroom activities. They also suggest that the quality of the play often relates to how well a child’s social skills are developed, which will then affects success in school. Forty-one children from Victoria, Australia (age 5-7) were assessed by five teachers with between five and twenty-seven years of teaching experience. Three scales were used Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment (ChIPPA, Stagnitti, 2007), The Leuven Involvement Scale for Young Children (LIS-YC, 1994) and The Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale (Fantuzzo, 1995). This article illustrates how imaginative play can aid in the development of social skills in children, and how the development of social competence assists in academic success. One drawback to this study is that the age of many of the children studied is older than most of the kindergarten students I am observing.

Focus statement: The way children play with Big Blocks is considerably different from the way they play with smaller sized blocks. The Big Blocks are located near the role playing centres, and are used in the creation of settings/props. Students use these centres to facilitate role play. While watching the children play, I noticed how the children were compromising and creating role play settings collaboratively.

Question: The kindergarten curriculum includes a strand for personal and social development. When kindergarten students play with the Big Blocks, in what ways is it helping them to build social relationships as they construct dramatic role play?

Reflection

At Phillips Avenue Junior Public School, Bill Wilson’s morning junior and senior kindergarten combined class, students are given at least an hour of activity time each day. During activity time, students can choose the activity they would like to do, with a few rules governing who and how many children can be at certain centres. One such centre, is The Big Blocks; children can play there, three at a time, no child can go there if they have played at the centre earlier in the week, and nothing can be built higher than one’s shoulder. At this centre, there are foot stool sized blocks that students can manipulate and use to create settings and dramatic role play. Given that the other role play centre in the classroom is a kitchen and dining room, the Big Blocks enable children to create new settings. By extension, this means that children might adopt roles they would not attribute to a house setting. For the purposes of this reflection, dramatic role play will be defined as “the presence of certain characteristics, including voluntary engagement, a lack of intrinsic goals, pleasureable effect and behavioural flexibility.” (Connolly and Doyle, 1984, pp. 798) During the time I observed The Big Blocks Centre, children had made an ‘aircraft carrier’, ship, big house, dog house and one student wanted to build a ‘rocket speed ship’.

The Big Blocks help to facilitate the communication of students in the social realm of role play through compromising, building settings collaboratively, communicating positively, appreciation and taking turns. The Kindergarten Curriculum contains a “Personal and Social Development” strand a sub-section for “Social Relationships.” In order for students to develop social relationships, they need to have multiple opportunities to learn the proper skills, exercise them and socialize. The Big Blocks provide a unique opportunity for students to participate in social activities that require skills of working well with others. The Kindergarten half day Curriculum cites the following as the expectations for Social Relationships:

12. Use a variety of simple strategies to solve social problems, 14. Act and talk with peers and adults by expressing and accepting positive messages, 15. Demonstrate an ability to take turns in activities and discussions, 16. Demonstrate an awareness of ways of making and keeping friends (e.g., sharing, listening, talking, helping; entering into play or joining a group with guidance from a teacher)

The four objectives were all observable in the behaviour of certain students on particular days, in The Big Blocks centre. Other centres also aided in the development of social skills, however the focus of this observation was on The Big Blocks, and how they related to constructing dramatic role play. Given the unstructured nature of the Big Blocks, students had multiple opportunities to communicate with their peers.

It is important to note that students have been taught social skills explicitly and implicitly during carpet time and presumably at home. Students are using social skills with some kind of support system and learning in place. Never-the-less, students try new skills and are likely learning social strategies from their peers directly, and possibly through a sense of developed and developing empathy.

At The Big Blocks Centre, students were not always working collaboratively or socially. Sometimes two or three students moved blocks individually, without discussing the process of what they were making or why. Often this issue could be alleviated by a teacher saying a simple open ended statement like, “Tell me about what you are building.” This would prompt a student discussion, “we are building a ship,” says Sarah. “No we are building a house,” pipes in Jerry. “Yes, a really big house,” Sarah states proudly.

Some days social relationships were strained at The Big Blocks centre, one child wanting to build and another child wanting to act in a dangerous way (swinging around blocks and climbing on top of them). So the amount and quality of social interaction resulted from: 1. the children present at the centre and 2. how those students were behaving and interacting on a particular day. On one occasion, two students collaboratively enjoyed destroying a building. Tod started knocking down Jerry’s house. Once Jerry made it clear that he was amused (by laughing) he began to participate. Sometimes social interactions and relationships were built non-verbally or without words. During times when students were actively destroying or being silly, of course the teacher (or myself) would intervene to insure student safety.

th, Terry T wanted to build an aircraft carrier. James wanted to build a ship. Terry T responded with, “ships are pretty tricky.” Eventually the two of them decided that they would proceed with the ship. Students would sometimes discuss the positioning of the different pieces. Furthermore, during the ship building students offered to help in the movement of blocks and asked if moving a block to a particular area was okay. When Sarah and Jerry were building a house, there were several times when they would express thanks towards each other for fulfilling a particular task. Some students would move blocks if they saw or felt that the block was in their peers’ way.

On the day Jerry and Lily were building a house, another student knocked over a part of the house. Rather than getting angry the two decided “We need to put this back together. We were just building it. We need to build this all over again.” Jerry offered his hard hat, “you can use this hat.” They then collaboratively began to build the structure once more. On this day, no role play occurred. Typically students did not start to role play, unless they felt their structure was completed. When Jerry and Aislinn were hammering at boxes, I asked them “Tell me about this.” Aislinn and Jerry co-created a story about racoons in the boxes. They expressed that the raccoons were trapped, that the mommy was lonely and told me the colours of eyes of the mother, father and babies.

Students would sometimes help each other in the sense of warning about different dangers. When the house was being built, a block was falling, Jerry noticed this and recognized the importance of his peer being safe. “Hey, watch out!” he exclaimed. When students play at Big Blocks, certain children are able to articulate that they did not like certain actions. Alvin once claimed that students saying that they would not leave the Big Blocks centre was “mean”. On another day Alvin said “Tod, I know you want to take the blocks off, but you gotta do it carefully.” Children communicate the ways that they feel safe, and the actions they would like their peers to take in the creation of role play settings. Children would often refer back to the rules, when playing, perhaps since it gave them a sense of safety and structure. Sometimes students would wander by and ask politely “Can I have turn playing here?” if three students were already playing in the area, a student at the centre would answer with the rule. In one case, a student reminded another in the shoulder rule. The students have been taught both the rules and how to protect each other. Cobb-Moore states that “children manage their interactive spaces through rule production and enforcement.” (1478) Often children would communicate with other students what the expectations and rules of playing with the Big Blocks were. The rules were designed to keep students. By teaching children what the rules mean and why they exist, when students remind their peers of rules in ways deemed socially appropriate to the student, perhaps it aids in the building of social relationships. Having a structured classroom with rules and having students know why these rules exist, helps students to solve social problems and articulate.

On the day when the aircraft carrier was built, after the construction, students engaged in dramatic role play. Not only did they discuss the building of the aircraft extensively (including rooms and proposed props within), the students collaborated in counting their ‘swords’ (represented by long blocks) and then identifying how large the swords were. Students designated where the various swords went, while sorting them into different sizes. Students also came to an agreement about the function of various props. For example, on one occasion a student claimed that a tube was for, “if anyone broke their muscle, this is new muscle.” Peers working with him at The Big Blocks, nodded in agreement.

During the dog role play, Terry T acted as a leader, however he was flexible with ideas from other students. He designated roles, however if students were not comfortable in a particular role, he allowed them to choose another or tried to re-allocate the roles in a way that satisfied all of the students involved. Students engaged in listening to and watching each other, in order to contribute to the role play. Over time the content of the role play evolved, as students decided to adopt new characters. Dramatic role play aids in building social relationships, as it requires that a child considers social situations from different viewpoints. (Connoly and Doyle, 1984, pp. 804) Students were then noting how their peers were changing their roles, and how the role play perametres were likewise shifting. Students needed to interact by considering both themselves as characters, and as individuals involved in a role play.

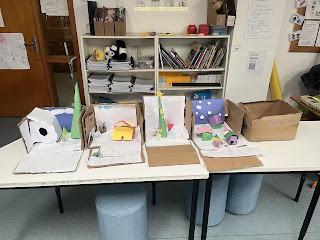

On November 30th, two students from the OISE kindergarten AQ were teaching an activity in the classroom. It revolved around the Big Blocks. They started by asking students what to remember when planning a building, wrote down student answers and then read the book “Construction Zone.” Students were then shown a white board, and pieces of different coloured paper with magnets on the back. They were shown that each paper represented a different size of block. Students were told that if they worked at the Big Blocks Centre on that day, they would make a plan for their building before executing it.

For the majority of my inquiry, I was more interested in the way students were communicating with minimal teacher intervention. Students are learning social skills in other contexts, and it’s necessary to see how they are using these skills for relationship building, with minimal teacher intervention. Sometimes, in order to facilitate conversation, I would ask open ended questions, which would aid in students deciding what they were building or how they could role play a certain scene. Examples for open ended statements included “Tell me about this”, “Can you explain this?”, “What will happen if…?”, “What will happen?” and “Tell me about your character.” I was curious how students would change their communication style with this activity. When three kindergarten students went to the big block centre, they began to play with tools and then began to arrange the pieces of paper, for their building. Students were not discussing the plans in the process of creating their building. Conceptually, they might not have connected that their plans would become a building. Although they did not communicate much aurally, the students did not move each other’s pieces of magnatized paper when creating their plan, instead focusing on the pieces of paper they were responsible for.

One reason for the students’ lack of communication, might have been the five adults watching three children. Two were doing the kindergarten AQ, there was myself and two parents. It’s also possible that they were not communicating since this was their first time doing the activity. The experience taught me a lot about the kind of teacher I do not want to be. One of the parents, seeing that her child was not creating the building, stepped in and led her child to the answer she wanted to see. Not only did it take some learning ownership away from the children, the children themselves did not come to a discussion about how to build, or what they could do with the resulting building.

Dramatic role play provides many positive aspects of social development among kindergarten students. The most important thing for a kindergarten teacher to do, with regards to this subject, is to provide settings, props and time for students to explore. Some props and settings should not be realistic, so a student can rely on their imagination to create meaning and purpose, perhaps creating a narrative with another student, as was the case when Tod declared a tube to be an item to “fix muscles”.

Children collaborate on sharing materials, exploring possibilities, making decisions, and developing stories that meet their interests. They share their experience and learn about the experiences of other children. They negotiate and compromise in order to keep the play going. When they come into conflict, they often improvise solutions. Pretend play is the children’s domain. For this reason, children at play are motivated to find ways of solving the problems that arise. (Drucker & Franklin, 1999, pp. 5)

A teacher can further aid his or her students in creating a safe and structured learning environment, where social relationship skills and empathy are taught, so that students can easily engage in group role plays.

Kindergarten teachers need to facilitate student learning, in socialization. One necessary aspect is in teaching how one treat friends, and in having students examine how they feel when they are hurt emotionally. Teaching students independence in their approach to most problems, is also necessary. Students in the observed classroom demonstrated a strength of actions and words that resulted in sustaining relationships. Many students were independently able to articulate what was bothering them and why that was the case. Many students were cooperative and helpful when fully engaged with their classmates. Rokockzy suggests that “pretend play can be considered as one of the areas in which children first learn to engage in shared cooperative activities, and in which they might even show and early appreciation of the ‘counts as’ relation.” (Rakockzy, 2006, pp. 113) Dramatic role play provides a vehicle for students to relate to others. Fantasy play should be included in every kindergarten classroom as it’s found to be, “more positive, sustained and group oriented than non fantasy play,” as participation in dramatic role play necessitates the use of complex cognitive and social abilities. (Connolly and Doyle, 1984, pp. 797) The fact that The Big Blocks are a free activity, gives children the ability to cognitively create while cooperating with their peers.

Given the short period of observation, I was unable to determine which children were perceived as ‘the most popular’. Rubin and Maioni (1975) referenced in the Connolly and Doyle article (1984), suggest that there is a correlation between occurrence of dramatic play and peer group popularity. Research also shows that children with poor pretend play skills are more likely to disrupt the class, and have reduced classroom involvement (Farver, 1992 pp. 501). Some children are naturally shier. However, if a child feels left out, feels unable to easily participate in activities with their peers and continuously engage in repetitive solo play, perhaps a teacher could consider trying an intervention. The habits of children with high dramatic play incidences and successful social skills might be observed. A teacher could try more directly teaching socially struggling children, providing that said children are developmentally receptive. High dramatic fantasy play children are generally more socially active, which involves a sustained, reciprocal and verbal response. (Matheson, 1992, pp.117) So, for students struggling with building social relationships, perhaps a teacher can suggest they spend some time at dramatic role play centres, with other students, and try to work with the student in ways that include that student in the collaborative process. For example the teacher could ask a social student to tell them about a structure or role play. The teacher could then ask a shy student to extend that and encourage story building/confidence building. The teacher would need to keep in mind not to pressure the shy child and make them feel comfortable. It is entirely possible that this method would not work, and this should not be seen as a failure on the part of the teacher or the child. Students need to be developmentally ready and comfortable to take ‘the next step’. “Reduced participation in play has a negative impact on children’s concentration and motivation in an academic environment.” (Bracegirdle, 1992 from Stagnitti and Uren) However, it should be noted that children are capable of creative solo play, and can learn a lot from personal explorations.

Stagnitti and Uren suggest the need for a play based behavioural assessment for kindergarten children, as otherwise social competencies cannot be easily measured. They utalized the Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment and The Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale (PIPPS). PIPPS contains items that are meant to assess a child in areas of strengths and weaknesses, it examines children’s social competency in play such as cooperatievness, helpfulness, creativity and on the flip side aggressive and anti-social behaviour. (Stagnitti & Uren, 2009, pp. 36) In the future, if I am teaching in a kindergarten classroom perhaps I could research and use these assessment methods or others. By engaging in ongoing assessment, teachers can develop a running record of social relationship building competencies. A major issue with assessments, however, is that judgement is very subjective. Independent assessment of social competencies can often be problematic, because pretend play is done in groups. (Matheson, 1992, 120) Adequate assessment strategies might aid in discovering the strengths of various students, how various students could improve in social relationships and potentially help their peers. It might also help a teacher to fashion potential strategies for intervention. Further research is necessary to examine ways in which I might probably intervene. Some teacher strategies for teaching personal and social development are outlined on page 21 of the kindergarten curriculum.

Given the results of my inquiry and research, obviously dramatic role play aids substantially in student social relationship development. Teachers should teach social skills, although I am unsure about the degree to which this should implicit or explicit. Students should understand the rules and why they are in place, as students themselves can then help to enforce them. There needs to be an emphasis of students working with each other, cooperating and compromising in dramatic play. Solo play is not anything to be alarmed about, however socio-dramatic play provides its own set of distinct advantages. Many students will develop skills required in social relationships, as a consequence of participating in socio-dramatic role play. “Developmental theorists speculate that the association between social pretend play and social competence with peers is due to the stimulation of cognitive processes through negotiation and enactment.” (Howes, Matheson and Unger, 1992, pp. 70, originally from Fein 1981, Garvey 1977, Rubin, 1980) Children also rely on strategies to make their actions and ideas shareable and intelligible with their playmates. (Farver, 1992, pp. 503) During social play children must acknowledge and develop suggestions/contributions of their peers. Role play and the creation of role play then helps to solve a variety of social problems both in and out of role, developing empathy and role taking. Social dramatic role play thus, directly supports the social relationship strand of the Ontario half day kindergarten curriculum. A teacher’s role should be in maximizing student interaction when attending these role play areas, and using the environment as a rich opportunity for social competency assessment.

Annotated Bibliography

Connolly, J & Doyle, A. (1984). Relation of Social Fantasy Play to Social Competence in Preschoolers. Developmental Psychology. Vol. 20, No. 5, 797-806.

In this study, ninety one preschoolers from thirty-five months old to sixty-nine months old were observed. Social competence was measured by teachers. It was found that the amount and degree of intricacy of fantasy play affected competence, which is described as “popularity, social role-taking skills, social competence and observations of social behavior.” A correlation between peer social fantasy play and the development of social skills / building of social relationships is suggested. This article discusses how social fantasy play differs from other forms of play, and the types of social fantasy.

Farver, J.M. (1992). Communicating Shared Meaning in Social Pretend Play. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 7, 501-516.

This article discusses the ways that children communicate shared meaning (or collaborate) during social pretend play. It addresses some skills that are required to engage in social pretend play with another peer, while creating a joint understanding of the narrative and objects involved. Forty children aged two to five are studied, with five pairs per age group. General differences in age related communication are also outlined, which is beneficial as most of the students I am observing are between four and five years old. This article is relevant to my own interests, as I am most interested in how Big Blocks helps to build social relationships through the collaboration of ideas.

Matheson, C. (1992). Multiple Attachments and Peer Relationships in Social Pretend Play: Illustrative Study #7. In Howes, C, Matheson, C. & Unger, O (1992). The Collaborative Construction of Pretend – Social Pretend Play Functions (pp.115-126) and Conclusion (pp. 133-138). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Half of this book dealt with early pre-school students, however in the second half of the book there are articles which mention the collaborative process children undergo in ‘social pretend play’. Collaboration can aid students in skills of flexibility and cooperation. Children also exercise a degree of trust when playing with their peers, and might use ‘social pretend play’ to disclose aspects about themselves that they might not otherwise feel comfortable expressing. This resource expands on the idea of fantasy social play promoting social skills and building social relationships and social competence.

Ontario Ministry of Education. Kindergarten Program, The. Retrieved October 22, 2011 from here

My observation will be focusing specifically on the social development that children undergo while playing with Big Blocks, especially as it relates to the Ontario Kindergarten Curriculum. This document will act as a guideline for what social development means in the Ontario Curriculum context.

Stagnitti, K. & Uren, Nicole. (2009). Pretend play, social competence and involvement in children aged 5-7 years: The concurrent validity of the Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 56, 33-40.

Stagnitti and Uren make the connection between play, the development of social skills and the ability to sustain involvement in classroom activities. They also suggest that the quality of the play often relates to how well a child’s social skills are developed, which will then affects success in school. Forty-one children from Victoria, Australia (age 5-7) were assessed by five teachers with between five and twenty-seven years of teaching experience. Three scales were used Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment (ChIPPA, Stagnitti, 2007), The Leuven Involvement Scale for Young Children (LIS-YC, 1994) and The Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale (Fantuzzo, 1995). This article illustrates how imaginative play can aid in the development of social skills in children, and how the development of social competence assists in academic success. One drawback to this study is that the age of many of the children studied is older than most of the kindergarten students I am observing.

Additional Sources

Cobb-Moore, Charlotte, Danby, Susan & Farrell, Ann. (2009).Young Children as Rule Makers. Journal of Pragmatics. 41, 1477-1492.

Curran, Joanne M. (Fall/Winter 1999). Constraints of Pretend Play: Explicit and Implicit Rules. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 14 no. 1, 47-55.

Drucker, Jan, Franklin, Margery B & Wilford, Sara. Understanding Pretend Play. A Guide for Parents and Teachers. A Guide to Accompany the Documentary Video “When a Child Pretends.” (1999)

Expressing and Exploring Issues of Control and Compromise by Negotiating Social Pretend Play Meanings and Scripts. In Howes, C, Matheson, C. & Unger, O (1992). The

Collaborative Construction of Pretend – Social Pretend Play Functions (pp.115-126) and Conclusion (pp. 133-138). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Rakoczy, Hannes. (2006) Pretend Play and the Development of Collective Intentionality. Cognitive Systems Research. 7, 113-127.

Comments

Post a Comment